“Sketches of Old New York”

Dr. Josué Ramirez

Summer 2010

1

“Sketches of Old New York,” is an art project focused on the 19th-century city. As an urban anthropologist I’m interested above all in what makes great cities great, and what helps their people remain creative and productive, and spiritually alive. I want to revisit the cultural innovations of the Industrial Revolution that heralded a democratization of everyday life. New York’s 19th-century transformation was in turn cultural and technological, including steamships and iron bridges, electric lights and elevators, talking machines and motion pictures, but also public schools and colleges, stickball and baseball, abolitionists and suffragettes. I want to see how these innovations were reflected in the energy of the city streets. “Sketches of Old New York” starts with a trove of old photographs now in the public domain. These images are my vehicle for a Whitmanesque tour of the old town. My current paintings are an emotional prelude to a long-term project on the anthropology of the metropolis. Most of the pieces in this collection are available for purchase by my readers and the general public.

My art and anthropology, of course, haven’t come out of thin air. In this essay I explain why someone with my background should take up the history of the city. Puerto Rican artists have typically not delved into New York’s past. For almost a century they have seen themselves as newcomers and outsiders. My desire to connect with the metropolis comes out of a specific generational perspective and from the moods and experiences of my early childhood. The premise for this project is worth sharing for its originality, and worth articulating at some length. In the pages that follow I describe the people I’ve met, the schools where I studied and taught, but also the ideas and values I have encountered about art and about life, and why, through it all, I remained an artist and a writer interested in art and the human condition.

2

This phase of my work has a special significance in relation to my father. I was born in New York in 1963 to Puerto Rican parents. I had four sisters, and was the only boy. My father came to the city in the 1950s from a village in the Caribbean. Perhaps because of its seemingly inhuman scale, he didn’t experience the city as a true community, or as a place with a verifiable history of suffering and striving. He never saw the city as I did. I can honor his life and immigrant struggle, but I have an entirely different generational quest. My paintings have been the basis of an ongoing conversation with my father about the nature and history of the city. As I start a career in anthropology, I realize that I am interested in the spiritual roots of metropolis. My theoretical orientation is in the tradition of Hegel and Weber, Simmel and Mannheim, but interestingly enough, my research interests go back to some of my earliest insights and to what I now see as a classic urban childhood.

“Immigrant Children, 1890s,” oil on canvas (14x20), 2009, (Offered at $2,200)

In my memories of the old neighborhoods I find significant pieces of American folklore, and specific urban customs that go back in the history of the city. I remember with fondness the games that we played on the city streets, games like boxball and hopscotch, jacks, tops and skulls, Double Dutch and Ringolevio, and especially that venerable continuum of ball games with a distinctly democratic feel: stoopball and stickball, softball and hardball. These were aggressive, highly competitive games, but they also instilled a timeless American sense of fair play. There were summers when we played baseball from morning to dusk, turning the sport into a veritable way of life. In the 1970s, we also played at war in abandoned buildings, on blocks that reminded outsiders of the ruins of Dresden. My earliest anthropological musings were about urban wreckage in the 1970s and its daunting human toll. I also remember excavating Buffalo nickels from cracks in the floors, and the yellowed pages from a 1922 newspaper found under old linoleum in the kitchen. The old city was all around us in the tenements. The scars on plaster walls and wooden doors spoke eerily to me of the dramas and lamentations of so many lost generations. These were the melancholy moods of my childhood. I was identified both at school and on the block as a gifted child, as a perceptive and highly imaginative artist. At an early age I made abstract compositions with the paint chips that fell from the old walls. I created an enormous and surreal web on my block from string I found in a dumpster. I drew portraits of famous Civil Rights leaders for school assemblies. I designed the stage sets for our class play. There were discussions among my public school teachers about having me apply for admission at one of the city’s art-oriented private schools.

3

In 1977, just as I entered adolescence, I was admitted at The Dalton School on the Upper East Side. I found Park Avenue breathtaking, but utterly inscrutable. Its fortress-like architecture was concealing and hermetic, and created an impressive silence on the sidewalks. Understandably, I had mixed feelings about the whole thing. Where were the street games? Well, at Dalton the children got their turn on the street at recess, but it was the briefest of turns. They could vent pent-up energies for just a moment before walking back upstairs for more lectures and exams. Park Avenue was a polite and self-controlled part of town, but the children seemed deprived of urban anarchies and adventures that had been so abundantly available to me in the nearby slums. The school, of course, wasn’t Park Avenue—though that was not entirely clear to me at the time. Indeed, it was founded in part as counterpoint to rigidities in the old Park Avenue elites. Dalton introduced a Montessori-inspired space in the 1920s, in which the natural creativity of your child might be encouraged, rather than repressed. By admitting someone like me, the school was showing its confidence that the Dalton plan was strong enough to be effective with practically any child. The results were interesting.

“Scholarship Boy,” self portrait, oil on canvas board (14 x 11), 1988 (Not on offer.)

I took remarkable history and literature classes, but the outstanding influence of my Dalton years was from the art program. I learned—as best as I can explain it now—a humanistic view of art that held self-expression to be at the core of individual and collective healing. The ultimate goal of art was to transcend our circumstances and reach for universal truths. And, there was something noncompetitive in this. Art and literature were personal and humble everyday practices to be cultivated throughout our lives. It was a modernist and supremely individualistic sensibility. Your art was to be a preserve of your unique personhood. This ethos of art once acquired, like good taste, tends to endure.

Even years later after being proven terribly impractical and naive in this, many of us remain artists and writers. As a high school senior, I was one of the founders of a school publication called “Another Perspective,” (along with Danny Arzuaga, Melissa Acosta, and others.) It was a student journal offering nontraditional views on current events. Years later on a visit to the school I was delighted to see that the journal survived, becoming quite glossy and international in its scope.

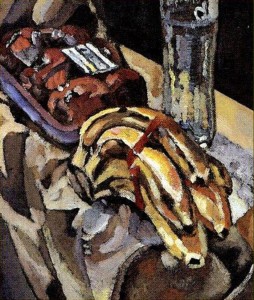

“Still Life in Rochester,” oil on canvas board (14x11), Summer 1987 (Offered at $3,200)

In college, however, I understood a special irony of schools like Dalton. They are vulnerable, not unlike other social sectors, to pernicious social stereotypes. What I call the school’s “art ethos” may—from a point of view of class resentment—appear wrapped in Manhattan privilege. It was always better to explain Dalton by rattling off things that were harder to misconstrue about the school. For instance, we learned to do a close reading of texts there, and to budget our time carefully on weekends. Because I was used to one-on-one conferences with Dalton teachers, in college I was a regular at office hours. These kinds of things set us up for success in college. I remember a paradoxical moment with Ms. Tyroler, our Russian literature teacher. In high school, my spelling was atrocious, but she told me not to let it bother me. She understood that English wasn’t my first language. She’d had students from Latin America over the years, some from rather exalted families, who were absolutely brilliant but had a tough time with spelling. “Now, proper spelling is important,” she said, “but it’s only one of the many components in good writing.” I might not have heard anything of the sort at a status-hungry, suburban high school. Ms. T wrote my recommendation letter to Brown.

Brown University, in Providence, RI, was my opportunity to meet the American middle class. My initial, and sturdiest, friendships were with other Latinos from schools like Collegiate and Trinity—Tony Nieves, Angel Bruno, Sonia Perez, Gil Maymi, and José Estabil. And, I met warm and caring students from wealthy families in Puerto Rico—Jaime Lluch, Miguel Trelles, Maria José (Pepa) Moreno, and José Roger. But, many of my most intense intellectual partners and confidants at Brown were from suburban, middle-class, often Jewish, families. They were from towns like Ridgewood, White Plains, or Chatham, NJ.

4

The “New Curriculum” of 1969 helps explain Brown’s stunning success in the 1970s and 1980s. Behind this initiative was Ira Magaziner, one of the great campus activists. The New Curriculum eliminated distribution requirements, and encouraged a self-directed, interdisciplinary attitude among undergraduates. Ranking at the top of American universities, Brown expanded its endowment dramatically, and attracted students like John Kennedy, Jr., who chose to forgo a family legacy at Harvard. The campus on the east side of Providence had an open, welcoming feel to it. I arrived during a vibrant, exuberantly “multicultural” phase of campus culture. Spanish House became my niche on campus. It was an elegant mansion on Prospect Street donated by the Sharpe family. Henry Sharpe, from a storied, manufacturing family, was a long-time chancellor of the university. Spanish House was, as I liked to say, “a magnet for campus intellectuals, creative types, and fellow travelers.” A number of my friends came with me from first-year dorms—Andrew Weinstein, David Kramer, Tammy Kaminer, Simone Jackiw, Suzie Gilman, and Nancy Wilson. David’s parents were a fascinating, intellectually active couple with whom I stayed in Rochester. Years later I shared an apartment with Andrew in the West Village.

“The Butterfly,” mixed media, oil on canvas with vintage Brown University football (24x40), 2000 (Offered at $4,200)

I became the publicist at Spanish House, and through edgy posters and flyers helped make it a campus hot spot. In one flyer I announced a “Coup d’état Party,” promising “praetorian singing and dancing,” and included a photograph of a Cuban army officer holding a little bomb. We packed them in that night, and charged admission. We hosted Craig Lively in the spring, with his campus rock band. Semiotics and Rhode Island School of Design students came to our events. Even professors in the Department of Romance Languages caught on and started spending more on their Friday tertulias at the house. Surprisingly, with clever flyers the genteel custom of conversational Spanish and sangria started becoming popular again at Brown.

My art at Spanish House was somewhat “magical realist.” Spanish House was where Borges spoke when he visited Providence in the 1960s, and where I imagine Nicanor Parra lived when he was a student at Brown. It was where the Argentine poet, Angel Leiva, held a poetry workshop that I attended in 1985. At the house I learned that a brazen attitude would attract others with an itch or inkling for experimentation. In those years, my work focused on faces. I did expressionistic studies of individuals. Art was a big part of my social identity, but it wasn’t just the thing on canvas or on paper, art was a social event, a conversation, a narcissistic milieu. Art was the social tonic that nurtured a broad network of relationships and desires. In 1985, David Kramer introduced me to Sarah Lum, a gorgeous and talented blonde from an old New Jersey family. She quickly recognized in my art a healing practice. As a Russian studies major, she was familiar with the writings of Kandinski and idealistic movements of Russian artists and writers. It was uncanny how two youngsters from such opposite backgrounds could meld together so passionately. If there were cynics at Spanish House, they kept their distance. Through my portrait work and intimacy with people from disparate backgrounds, I had begun, without knowing it, to think of the world in anthropological terms.

My room at Spanish House, with Sarah Lum, 1985

5

As I gained confidence at Brown, I became known as an academically ambitious student. I studied American and European intellectual history, and was awed by the historians on campus. Mary Gluck, whose course on 19th- and 20th-century European thought was foundational for students in a range of fields, took an interest in me. I wrote for her an “intellectual autobiography” as an alternative assignment, and she later told me that reading it brought her to tears. I felt a special bond with Mary after that. She contemplated my writing on poverty and urban suffering, and gave me an interesting piece of advice. I wouldn’t say this to other students, she said, but you should consider—try to understand and perhaps be open to—of all things, the middle class. It was a succinct idea—to think of the middle class as a haven, as a generational attainment, as a class location in which to catch my breath in, to settle down in. She was thinking ahead, of course. I put the idea away for many years.

The history department was my academic home. But, my undergrad mentor was Martin Martel, an old theorist in sociology. Martin had been one of Ira Magaziner’s advisors in 1969. He’d been involved with the NAACP in the 1940s, when it was still considered dangerous work. He’d grown up in mob-ruled Miami when it was tough to be Jewish and active in the south. He was the only professor in living memory who smoked in seminars. Hardly any smoke came out of him. He died in 1996, at the age of 67. I took grad-level theory with Martin, reading Weber, Freud, Mannheim, Parsons, Habermas, Bordieu and Foucault. The education I received from Martin gave me the theoretical heft to deal with the complexities of urban culture as an anthropologist. In 1986, Martin recruited me for “SPECTRUM,” a student-faculty group studying campus life and diversity issues at Brown. I became a spokesperson for SPECTRUM and helped present the group’s findings to the Brown administration in the fall. It was one of the highlights of my undergrad career.

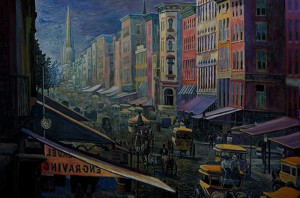

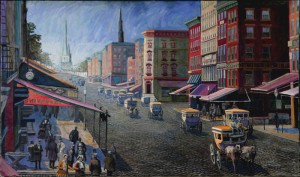

“Broadway Traffic, 1859, no.1,” oil on canvas (26x42), 2009 (SOLD)

6

Greenwich Village (1988-1991) was a wonderful interlude in my life. I shared an apartment with Andrew Weinstein on the corner of Bleecker and Grove. Andrew was a caring friend, who was working on a writing degree at NYU. I had a job at a 5th-Avenue insurance company. Those were healthy years in which I dated several remarkable women, including Julie Rosenberg. And, slowly but surely I started to feel the pull of academia. I found myself spending weekends in Washington Square Park, taking copious notes. It was uncanny—but the purpose of my notes wasn’t yet clear to me. In my own haphazard way, I was in fact beginning to write anthropology. I met, for instance, an eighty-year-old blind sculptor, a member of Jackson Pollack’s postwar circles, who filled her conversations in the park with kindness and openness. She had never stopped working, never stopped being creative and productive. I was interested in theorizing urban diversity and the interaction of sectors in the city. Art continued to be a big part of my post-college identity, and part of my everyday routine. I painted collages of people on the streets, and a large canvas of the Statue of Liberty morphing into Michelangelo’s Moses. It was an exploration of 19th-century iconography and the meaning of classical idioms in the emerging metropolis. I also reconnected with a high school friend, Sabin Howard, who was pursuing a career in classical sculpture.

When I returned to Brown as a graduate student in 1991, my goal was to develop a new anthropology of the emerging city. Anthropological training offered a broad perspective on human cultures. I yearned for the holism and immediacy of ethnographic fieldwork, and for the adventure of finding my subjects in the field. I wanted to focus on emergent urban sectors, and on cultural innovators in particular—creative artists, writers, performers, musicians. It was a way to bring art and anthropology together. The title of my master’s thesis was: “The Artist and the City: Multiculturalism and Gentrification in the East Village” (1994). It was based on summer fieldwork in the East Village and the Lower East Side. I interviewed two dozen middle-class artists, and compared those interested in interacting with those who wanted to avoid urban diversity. For my doctoral work, however, I took on another quite challenging topic, the problem of “machismo” in Mexico City. It was ostensibly a study of gender and social change.

My doctoral work in Mexico City focused on a technologically oriented, primarily middle-class population. The title of my dissertation was “Against Machismo: Young Adult Voices in Mexico City.” It was published as a monograph by Berghahn Books in 2008. I conducted 74 open-ended, life history interviews, looking closely at how Mexicans used the word “macho.” After a long analysis, I concluded that the Mexicans in my sample were engaged in a “critical reevaluation” of gender and family life. In contrast to the pessimism of recent writing on Mexico, I argued that the patterns I document in my ethnography represent “progressive change.” My dissertation was remarkably successful. Professor Michael Herzfeld, of Harvard, served on my dissertation committee. And, through the most difficult years of graduate school, I continued to paint.

“Waterplace Park, Providence, RI,” oil on canvas (20x60), 1997 (SOLD, signed prints offered at $120)

In the summer of 1997, the city of Providence opened Waterplace Park, an extraordinary waterfront development that helped spark a revitalization of the city. One weekend I went down to the waterfront with several rolls of film. I decided to paint a large panorama of the new waterfront, and as soon as word got out of the project it started to receive the attention of the city’s business establishment. Overnight I became “a prominent local artist” in the local press. I understood this turn of events in anthropological terms: There are images, I explained to the various corporate executives I met, images that represent collective aspirations. But, artists coming out of the art schools generally don’t work with such images. They are trained in a different mode of self-expression. Though the Rhode Island School of Design was literally along the waterfront, most of the students there would not paint the city in front of them. They were not attuned to a broader civic space, and certainly not to the dreams and aspirations of the people of Providence. My new work was thus a melding of art and anthropology. It was an art project with an overtly anthropological premise. I was drawn to the waterfront because I sensed that it represented a healing for the city. The river had been covered over with concrete and asphalt for generations. Now the wound was being repaired, the scar being removed. My closest friend in Providence was Kathleen Galek, who would become a Buddhist psychologist. I shared with Kathleen an ongoing conversation about healing and spiritual health.

My portrait of the waterfront was featured in the Providence Journal, and the Rhode Island’s main business monthly. I was invited to participate in the annual gala at the Newport Tennis Hall of Fame, where one of my pieces was auctioned for charity. I had the chance to meet Maxwell Mays, perhaps Rhode Island’s leading painter. We had a long talk at his estate in Little Compton, RI. My panorama of Providence was my first attempt at a cityscape, and it was an enormous success. It was purchased by Andy Mitrelis, long-time owner of Andrea’s restaurant on Thayer Street. Several years later, one of his customers offered him five times what he paid for the painting. But, Andy said he would never sell it. “Waterplace Park” was the start of my interest in cityscapes. After graduating in 2002, I taught at a range of colleges in Massachusetts, including Harvard and MIT. From 2004 to 2008, I was an Assistant Professor at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. When I returned to New York in 2008, I took up cityscapes again. And, this time I sought to discover old New York through classic images—photographs and prints—of this extraordinary metropolis.

7

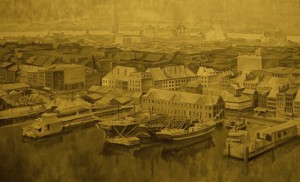

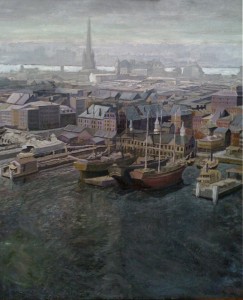

On January 12, 1876 Joshua Beals, a Manhattan photographer, carried a bulky box camera to the top of the newly completed Brooklyn tower of the Brooklyn Bridge. He took five separate glass-plate photographs of the city, creating the first aerial view of New York. It captured the city at the cusp of its great explosion into the air. The Brooklyn Bridge itself was a demonstration of what was then possible. Over the course of the 1870s, it showed astonished New Yorkers what could be done with cast iron and steal beams. Civil engineers and architects all over town could see in Beals’s print a potential city behind the bridge. It was a city with aspirations, a city with a remarkable future. In the fifty years from 1870 to 1920, New York rose to rival and then surpassed London as the leading financial center in the world. Beals’s image, however, shows a large but low-scale city of modest architecture. The French-inspired buildings on Broadway were more ambitious, but in the main New York buildings were utilitarian affairs, factory-like constructions concerned with the bottom line. This plain aesthetic, ironically, would add substantially to the city’s modernist turn in the decades to come. It was also a city of gritty, weathered determination, a vibrant city that continuously built itself upward, adding hundreds of thousands of immigrants every year.

Joshua Beals’ 1876 Panorama of New York

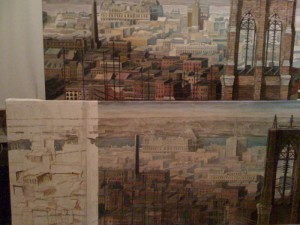

When I returned to New York in 2008 I went to see my old friend, Sabin Howard. He was now much further along in his career as a classical sculptor. As always, Sabin was thoughtful and supportive. I asked him if he knew of a landscape painter in the area that I could learn from, and as it happened, he did. Her name was Kathy Coyle, and she and her husband lived on a farm in New Paltz. She was a classically trained master painter and took on students once in a while. This was the start of my project on Old New York. I went to see her once a week to work on technique and to hear her talk at length about light and shadows, color values, and a vast collection of personal insights on painting. She was an extraordinary instructor, and not surprisingly, she was also a healer. She was not enthusiastic about working from old photographs. That is simply not what a classically trained painter would do. But she thought it might be a vehicle to teach me technique and deepen my sense of the canvas. The resulting works, however, started to take on a life of their own. The first exercise I did with Kathy was a traditional “Grisaille,” or grey sketch, of old New York.

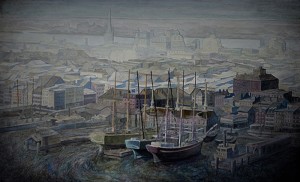

“Old New York, 1876,” grisaille, 2009 (Not on offer)

Kathy and I then worked on color values, the foundation of traditional landscape painting. And, I started to define my aesthetic goals with more precision. I sought to capture the gritty, sooty, weathered feel that comes across to me so powerfully through Joshua Beals’s panorama. I also wanted to retain some of the naïveté of 19th-century New York painters—a quality of the city’s aesthetics from its humble, early days as a colony. For centuries, however, emerging cities like New York looked to Paris for inspiration and refinement. And in Paris in the 1870s, the Impressionists were arguing for a fundamental relaxation of Western art. It was, unmistakably, a democratizing trend in world art, and one that fit especially well the casual, democratic, bustling spirit of New York. This connection I didn’t want to overlook. I came to the conclusion that rather than a focus on the kind of architectural rendering found in much of classical painting, what I wanted was to capture a mood, an impression of old New York. And, though weathered, sooty and workmanlike, it was the optimistic mood of a city on an extraordinary rise to the top.

“Old New York, 1876, no.6,” oil on canvas (26x42), 2009 (Offered at $3,200)

Each of the subsequent pieces was unique, each a somewhat different meditation on the theme. Working with Kathy was intense and challenging. We would sometimes battle over changes to the work. I might take a painting home, re-stretch it, sew on more canvas, and then return with it to New Paltz, to the howls of Kathy Coyle. It was a tumultuous year of teaching and apprenticeship. Ultimately, I saw the work that was emerging as Whitmanesque—it was about a wisp of water in the harbor, a curl of smoke, the glare of sunshine on rooftops. There was a little ash can in it, a little romantic landscape, a little nostalgia, and above all, a celebration of the survival instincts of a port town, and the remarkable energies that helped build it into a successful metropolis.

“Old New York, 1876,” no.4, oil on linen (cropped to 26x42), 2009 (Best in series, offered at $6,200)

“Broadway Traffic, 1859, no.3,” oil on canvas (26x42), 2010 (Offered at $4,200)

Detail, “Brooklyn Bridge, 1876,” nos. 3 and 4, oil on canvas, 2010 (Work in progress)

“Broadway 1849, after Paprill’s View,” oil on canvas (26x42), 2010 (Work in progress)